Happy birthday, Benito Juárez, the biggest president in Mexico

Each March 21, Mexico celebrates the birth of Benito Juárez, the boy of Zapotec who has become president, hero and Symbol almost all Mexican. The schoolchildren memorize his words, the politicians invoke his name and his severe face looks at statues across the country. If you have a peso, you probably have Benito Juárez in your pocket right now.

Juárez was born in 1806 in the small village of San Pablo Guelatao, Oaxaca, a place so quiet that you could hear a tortilla switch to a mile distance. He only talked about Zapotec until the age of 12. Orphan at three years old, he was, by all testimonies, a calm and serious boy.

But he learned Spanish. He studied law. And then, in one way or another, he overcome his humble beginnings and changed the fate of a nation. He became president not once, not twice, but five times. He rejected the European invaders. He pushed reforms that would put power in the hands of the people. And he did everything with the charisma of an overworked accountant.

A turbulent start in politics

Juárez made a trip to roller coaster to become the unshakable chef of Mexico. He got involved in the policy of the Liberal Party at the start of life and was elected governor of his original state in 1848, a role in which he made an enemy of Antonio López de Santa Anna. When Santa Anna returned to power for the last time in 1853, Juárez was imprisoned and exiled for his liberal opinions. It was not the first time he would have been on the run in the coming years.

Juárez fled to New Orleans, where he spent two years in darkness, working as a manufacturer of cigars and plotting the future of Mexico with other exiled liberals, waiting for the right time to go home. This moment came in 1855, when Santa Anna was overthrown in the Ayutla revolution and Juárez returned as Minister of Justice New liberal government that would shape the future of Mexico.

The reforma and the constitution of 1857

Juárez was, at the base, a reformer. He believed in laws, institutions and, above all, that a country had to belong to his people, not to the Church or to a handful of elites. He put pressure for reforma, a series of laws that separated the Church and the State, confiscated the church and the indigenous lands belonging to the community and tried to transform Mexico into what the Liberals considered a modern republic, kicks and cries if necessary. The juárez faction of the Liberal Party wrote the Constitution of 1857Incorporating these provisions such as the law linked to the land.

Naturally, it put a lot of powerful people very angry. The Catholic Church, which has been directing things for some time, suddenly found itself at the end of history. The conservative elites, who preferred their obedient and illiterate peasants, considered Juárez as a dangerous man. And when Mexico’s ruling class becomes uncomfortable, history tells us that they generally do something radical.

The war of reform and the second French intervention

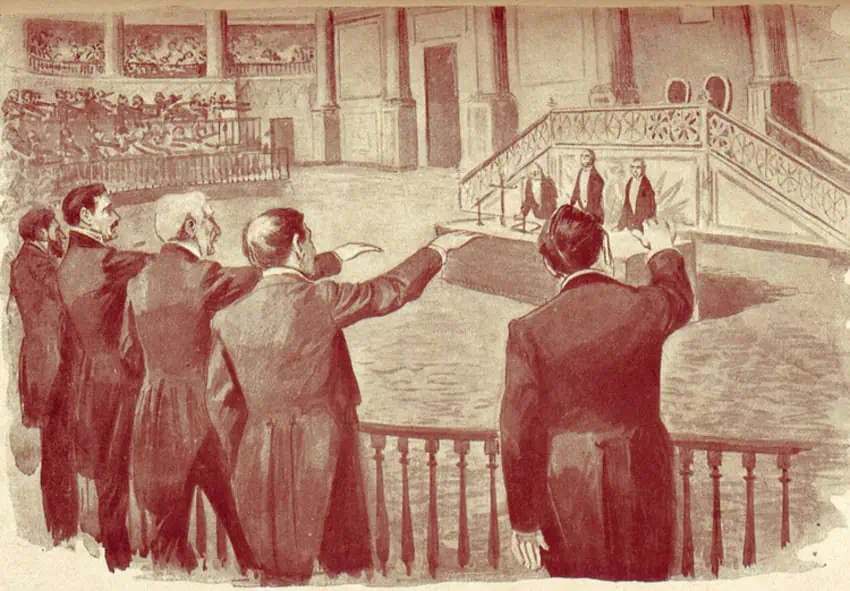

In December 1857, the Conservatives rebelled against the new Constitution, convinced the liberal president Ignacio Comonfort to overthrow her own government and Plunged Mexico into civil war. As chief judge of the Supreme Court, the presidency was legally adopted in Juárez, who led the Liberal government to the military victory against the conservatives in 1860 and easily won the presidential elections of 1861. But the conservatives have not yet been defeated, and they still had a round of their round.

Enter Maximilian von HabsburgA well -dressed Austrian sent by Napoleon III to govern Mexico. With the support of the Mexican conservatives, France installed Maximilian as an emperor, and suddenly, Juárez found himself again by directing a fascia government, chased through Mexico by a man who had absolutely no business.

Did Juárez abandon himself? No. Did he conclude an agreement, because Maximilian proposed it? Absolutely not. Instead, he led guerrilla warfare against the conservatives and the French. And when the tides turned and Maximilian was finally captured, Juárez made her try and executed. No exile, no second chance. Just a shooting team and a clear message: Mexico would no longer be a European colony.

Juárez had won. He had fought for democracy, for the people, for a government free of foreign corruption and influence. But then came the delicate part: governing at a time of peace.

The restored Republic

Like many big revolutionaries before him, Juárez discovered that the management of a country is much more difficult than fighting for one. Its reforms, such as Lerdo’s law, had to break the community Aboriginal land to create private property and stimulate the economy – in reality, the rich landowners and speculators bought most of the newly private land.

Although noble in principle, these reforms have often made more to alienate people than to unite them. The poor rural people, many of whom had joined the forces of Juárez during the war, did not necessarily see their lives improve under his direction. The injured but still powerful church continued to resist it. His enemies in the government accused him of clinging to power, of ignoring dissent, of being as dictatorial as the men against whom he had fought.

However, Juárez did not stop re -election, often against strong opposition from other liberals. He centralized power in a way that made his nervous allies. Some of his closest supporters defected and even revolted against his government in 1871, including, ironically, Porfirio Díaz, the general who would later govern Mexico as a dictator for more than 30 years. The revolutionaries had become the establishment. And like so many people before him, Juárez started to look less like a radical reformer and more like a man who simply could not let go.

Benito Juárez always kicked

In 1872, Juárez died of a heart attack at his office. His inheritance, however, refused to rest. Today, Benito Juárez remembers himself like Abraham Lincoln of Mexico, a man of people who believed in justice and equality. His face is on money. His birthday is a national holiday.

And yet, Mexico is still arguing about it. They discuss his reforms, his decisions, his stubbornness. Some call him a hero. Others, a tyrant. It is perhaps because his difficulties always feel so present in Mexico. In some respects, the battles he has fought – between rich and poor, liberal and conservatives, progress and tradition – have never really ended.

Stephen Randall Comes in Mexico since 2018 by Kentucky, and before that, Germany. He is an enthusiastic amateur chief who is inspired by many different kitchens, with favorites such as Mexican and the Mediterranean.