No Mexico City route is complete without visiting Chapultepec Park, the vast urban wood which contains some of the country’s largest monuments, museums and art galleries in the country. For a park which offers such tranquility in the middle of the frantic rhythm of the city, it is difficult to imagine the effusion of blood which took place there during the American-Mexican war from 1846 to 1848.

Towards the end of the war, on September 13, 1847, around 2,000 American soldiers led by General Winfield Scott stormed the castle of Chapultepec, which at the time housed the military academy where the army cadets formed. It was a decisive American victory that turned out to be crucial to the American occupation of Mexico Subsequent annexation of the territories of northern MexicoIncluding Alta California, Arizona and New Mexico.

In the American collective imagination, the invasion of Mexico receives much less attention than the civil war which followed a little more than a decade later. But the war was essential in American history: it helped to consolidate the expansionism of the country of the North and gave a political and geographic weight to the doctrine of manifest destiny. Events such as the Battle of 1836 of Alamo – a technically part of the Texas Revolution – are more widely known, perhaps because it was a loss. The defeat invites the story, giving people a reason to cry, rally and mythologize.

In the Mexican national conscience, the Battle of Chapultepec remembers the heroic acts of the Niños Heroes (Boy Heroes), six cadets of the Academy who would have disobeyed General Nicolás Bravo. Agustín Melgar, Fernando Montes de Oca, Francisco Márquez, Juan de la Barrera, Juan Escutia and Vicente Suárez fought to defend the castle. Escutia, the last surviving cadet, would have enveloped himself in the Mexican flag before jumping from the castle when he died to prevent American forces from capturing it.

The names and exploits of the Niños Heroes are learned by Mexican schoolchildren as part of the national program established by the Ministry of Education. We remember him like valiant martyrs who dodged bullets and bayonets, preferring to die for their country than to go to the pervasive forces. “The message was to love your country to death,” said Adolfo Zambrano, sociologist at the University of Bielefeld, in Mexico News.

In Puerta de los Leones, the main entrance to Chapultepec, the Patriot altar brilliant white (AUTEL AT THE PATRY) is in view of the wrought iron doors. Built between 1947 and 1952 in Italian marble, this monument commemorates Mexican life lost in the American-Mexican war. The six cadets are represented by imposing pillars, each crowned with an eagle and a torch pointing the sky. In the center of the monument stands the homeland, personified by a muscle native woman rocking a young man fell draped in the national flag. Look closely beyond the monument and you will see Castle of Chapultepec perched on the hill directly aboveWith the same flying flag of its peak – a symbolic recovery of the story, quietly denying that the American flag has ever stolen there.

Fact, fiction and historical ambiguity

Through Mexico, in almost all cities and cities, streets, squares and even bus stations bear the names of the Niños Heroes. Although their history is widely shared, the separation of fiction facts is more difficult. Myths surrounding the cadets have long been accepted as a historical truth. For example, official government sources always claim that they were the last defenders of the castle, despite a lack of evidence. Their names, now sculpted in stone, only appeared in a history book in 1883, 36 years after the battle.

To begin with, the idea that the cadets were children are misleading. While two were under the age of 18, the other four were young adults, including Juan Escutia, who was 20 years old. Juan de la Barrera, 19, actually held the rank of lieutenant among military engineers. Refer them as boys hang on the emotional resonance of their sacrifice and positions them as ambitious personalities in the national imagination, strengthening the values of duty, loyalty and patriotism.

Their juvenile image does more than raise them as models. The innocence projected on the Niños Heroes reflects the childhood of the Mexican Republic itself. Barely two decades after having obtained the independence of Spain, in Mexico, in the 1840s, a fragile and deeply divided nation has difficulty defining itself against internal conflicts and foreign aggression. The story of six brave young cadets, young and overwhelmed, standing against a powerful force of invasion, has become a powerful allegory for a nation hung on sovereignty.

Some criticisms wondered if the six naños heroes existed in the form that we remember today. However, the historical stories suggest that around 50 cadets, in an act of challenge, remained at the castle of Chapultepec to fight alongside the Mexican army. Although their decision was reckless, it was cropped as an act of bravery and patriotic sacrifice.

The Battle of Chapultepec was officially commemorated for the first time on September 13, 1882, during the presidency of Manuel González Flores, the period of four years of indirect rule during the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz. The ceremony inaugurated the monument of Obelisco in Los Niños Heroes, which is still at the foot of the castle of Chapultepec and was designed by Ramón Rodríguez Arangoiti, itself one of the cadets captured during the battle. This tradition is continuing today: each year, on September 13, the president reads the names of the Niños Heroes at the Alument of the altar A La Patria.

Has Juan Escutia really wrapped in the flag?

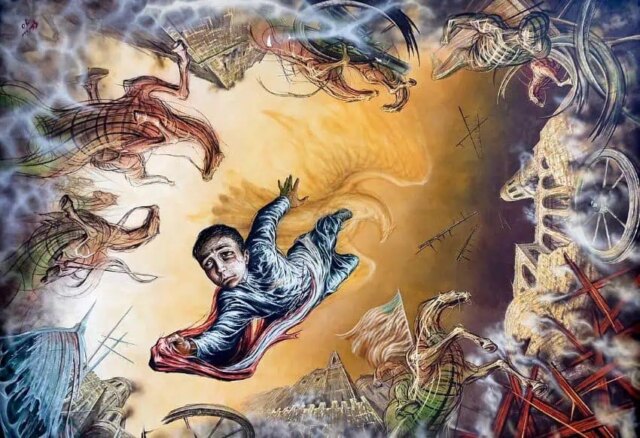

The castle of Chapultepec is now a museum, largely preserved as it was during the reign of the Emperor Maximilian under the French occupation. Visitors who climb the winding upward path will find more realistic statues of the Niños Heroes. On the central staircase of the castle, a 1967 ceiling fresco by Gabriel Flores represents the jump of Juan Escutia at his death, wrapped in the Mexican flag. But has it really happened this way?

The evidence suggests that the escutia was perhaps not at all a cadet, but a soldier of the Battalion of San Blas. This unit, founded in Nayarit in 1823, was directed during the battle of Chapultepec by a less known figure by the name of Felipe Santiago Xicotéencatl. According to Eyewitness testimonies, Xicotencatl was shot down by American forces while trying to keep the flag of his battalion at altitude. As he fell, his comrades wrapped his body in the flag and buried it with it.

The story of Xicotencatl may have been transferred later to Escutia, which was redesigned as a boy to increase the drama. In 1947, the remains of Xicotencatl were exhumed and finally buried alongside the remains of six people found in Chapultepec and presumed to be the Niños heroes under the altar at the Patia Monument at the entrance to the Park – another assertion which turns out to be difficult to support.

In particular, Xicotencatl was native, an officer of Nahua from Tlaxcala, while the Niños Heroes are almost always described as Cadets with clear skin and Europe. This contrast reveals how post-independence Mexican nationalism often favors a Europeanalized ideal of citizenship. By transferring the history of the patriotic sacrifice to Juan Escutia, a reinvented figure as youth and white, the myth has erased the contribution of the Aboriginal person.

What do the Niños heroes tell us about Mexico?

Whatever the part of their history, the lasting prominence of the Niños Heroes reflects the need for the start of the nation state to transform the accounts of loss and sacrifice into unifying myths. Their legend offers a consolation for the loss of almost half of the national territory of Mexico following the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 and continues to have an emotional resonance for the Mexicans today. Recalling his childhood in a 2005 essay, the literary criticism of Mexico City, Guillermo Sheridan, remembers the influence of the Niños Heroes: “that there could be boys who, in addition to being boys, were heroes, was added to a pressing demand on my own potential heroism. scoundrel. “The power of history lies not only in what he commemorates, but in the way he continues to shape national identity. As Adolfo Zambrano said of Bielefeld University,” there is part of me who believes that the myth has really happened despite the lack of evidence. “

When we hear about the renewed expansionist ambitions of President Donald Trump, it is tempting to treat such rhetoric as an anomaly. However, a more in -depth examination of this period of Mexican history reveals that the territorial aggression has long been a principle of American foreign policy. The wounds of American-Mexican war are deep in the collective memory of Mexico, and they continue to shape the way the country understands its relations with its neighbor in the North. The myth of the niños heroes is a means of treating this heritage – overhaul the defeat not as a humiliation, but as a heroic model of sacrifice.

Shyal Bhandari is a British-Indian writer taken in a swirling romance with Mexico. He holds a MPHIL in Latin American studies at the University of Cambridge. His writing appeared in publications, in particular Vogue,, Ojarasca,, Little White Lies And Asymptote newspaper. In 2019-2020, he organized a series of literary workshops with Aboriginal poets in southern Mexico with the support of the Royal and Old International Stock Exchange.