Why do the Mexicans say sorry all the time?

When I started going out with my current partner, I had several Uncomfortable moments with her mother. Born and raised in the Soviet Union, she just didn’t understand why I kept saying “I’m sorry” or “excuse me” whenever I was on her way or accidentally stumbled on her. As an clumsy person myself, it came naturally. However, when she clearly asked why, I couldn’t answer – immediately, at least. She was obviously uncomfortable with the question, which only made you get worse for me.

At first, I simply attributed this to the fact that I was raised as a “polished” person in a typical Mexican family. For her, who spent most of her life in a Soviet environment where people – and women, especially – do not say sorry unless something is definitively bad, the use of expression was simply not necessary. In other words, it was a confrontation of cultures. However, it was not the first time that this discomfort has appeared.

I have the great chance of working with people from the United States for a long time, especially in the editorial roles that I have undertaken for most of my career in journalism. When there have been misunderstandings or bad communication problems, my personal instinct was to say: “I’m sorry” – as was for my Mexican teammates.

Foreigners sometimes find this excessive. Some of them simply said, “Oh, don’t say sorry!” I guess they understood the cultural gap. The question, however, remains: why do the Mexicans say that we are sorry all the time? The answer is much more complex than I envisaged in the first place and has its roots in the colonial / Catholic past that we carry from the cradle.

What are we, Mexicans, sorry?

The Mexicans are proud of the fact that we are polite, friendly and warm. In our minds, we are the perfect, super funny hosts and simply the best company we can keep. Even if people from other parts of the world believe that we are welcoming, part of our “politeness” is not well understood by people from abroad.

Psychiatrist Carl Jung once said that “the content of the collective unconscious is mainly made up of archetypes”. AThe rchetypes are Diagrams of thought and behavior which generally come from the context or the environment of an individual, namely the mental representations of the social phenomena which we do not know exactly, but which we certainly feel unconsciously. In Mexico, some of the largest archetypes come from the fact that we are intrinsically Catholic. Let me explain to me.

Even if my partner was raised by a Soviet mother, who learned that “Religion is the opium of the people“I have often heard it say:” ¡Gracias a dios! “(Thank goodness!) With great relief.

“ Ask forgiveness ” is a religious affair in Mexico

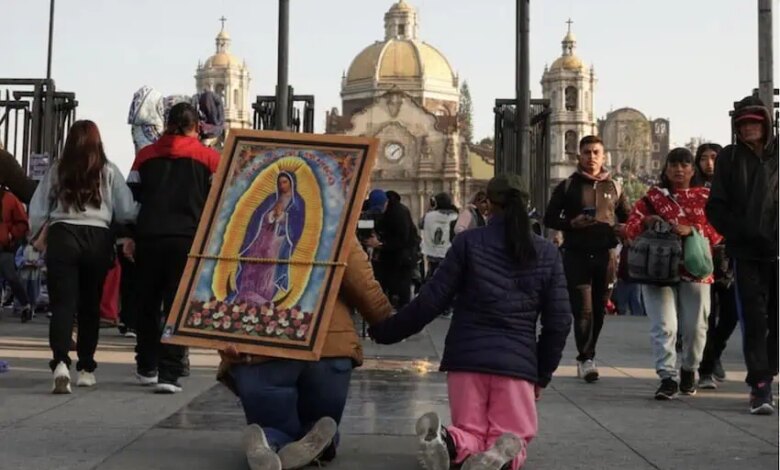

And how could he not? In a country at 77% Catholic, by The latest Figures of InegiWe, Mexicans, coexist with Catholic values all the time, as if they were anchored in our spirits of the uterus. Our references are intrinsically Catholic. In all corners of Mexico City, as in practically all Mexican cities, people place altars dedicated to their saint of choice. Cholula, in the central state of Puebla, has more churches than schools – 365 Catholic temples, to be precise, according to Universidad de Las America, Puebla (Udlap). Men and women are named ‘Guadalupe“For the love of Christ.

As you may have guessed now, People in Mexico fear God. This does not mean – not exactly, at least – that we are afraid of an all -powerful entity. On the contrary, according to Bethlehem College and Seminary Scholar John Piper, this implies a feeling of fear and respect for the Christian God. And submission. Especially submission. Given the Christian principle that we were born from sinners and that God forgives our imperfection, we are told that we must ask for his forgiveness – each time.

Growing up, I remember that my mother urged me to confess my sins during Sunday service. After having enlisted them all at Confessiony – God does not like it! The child did not do his homework – the priest insisted that I sincerely ask God to forgive me. I am almost sure that seven in ten children in Mexico had similar experiences growing in Catholic households.

This religious practice is almost naturally reflected in the way in which we relate to each other. As much to ask for the grace and forgiveness of God, Mexicans – and people from all countries formerly colonized in Latin America – feel the need to make our social defects in reaching by reaching forgiveness of the other.

In this context, “the other” is understood in psychoanalytic terms: an entity that exists beyond oneself and represents the moral duty and the values of a society. Given the vertical arrangement that we observe towards God – Catholic practitioners or not – it is fair to say that we grant the great Mexican morale to the other.

We, Mexicans, are subject to others, and often sacrifice our own needs and desires to restore social order. The way to rectify our mistakes, whatever the severity, asking for forgiveness. It is even expected Of you, if you are polite and willing to maintain certain personal and professional relationships.

Seen in another way, the Mexican way to regenerate the social fabric could very well be by asking for forgiveness. It is well known that we are a culture of ancient rituals. Asking for forgiveness may be only another of them, deeply influenced in the colonialist past which still weighs on us as culture and society.

¡Qué Pena! – We say a little too “sorry”

So now you know. The next time you hear someone say, “disculpe”, “qué pena”, “una disculpa” or any other interjection of forgiveness, you also have an anthropological experience. If these faults are not resolved, guilt comes into play. But the question of guilt is only another whole article in itself, sorry!

Andrea Fischer contributes to the office of the features of Mexico News Daily. She edited and wrote for National Geographic in Spanish And Very interesting MexicoAnd continues to be a defender of everything that screams science. Or yoga. Or both.